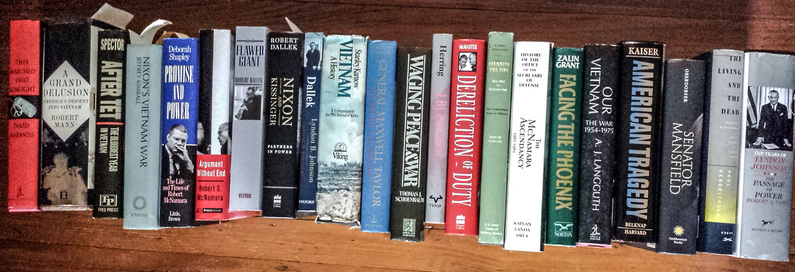

Partial list of the books using Dr. William Conrad Gibbons' research

(from left to right in the photo above):

They Marched Into Sunlight by David Maraniss

A Grand Illusion - American's Descent Into Vietnam by Robert Mann

After Tet - The Bloodiest Year In Vietnam by Ronald Spector

Nixon's Vietnam War by Jeffrey Kimball

Promise and Power - The Life and Times of Robert McNamara by Deborah Shapley

Argument Without End by Robert S. McNamara

Flawed Giant by Robert Dallek

Nixon and Kissinger - Partners in Power by Robert Dallek

Lyndon B. Johnson - Portrait of a President by Robert Dallek

Vietnam, A History by Stanley Karnow

General Maxwell Taylor - The Sword and the Pen by John M. Taylor

Waging Peace & War by Thomas J. Schoenbaum

LBJ and Vietnam by George C. Herring

Dereliction of Duty by H.R. McMaster

Combat Operations - Stemming the Tide by John M. Carland

The McNamara Ascendancy - History of the Office of the Secretary of Defense by Lawrence Kaplan, Ronald Landa and Edward Drea

Facing the Phoenix by Zalin Grant

Our Vietnam - The War 1954-1975 by A. J. Langguth

American Tragedy by David Kaiser

Senator Mansfield by Don OBerdorfer

The Living and the Dead by Paul Hendrickson

The Years of Lyndon Johnson - The Passage of Power by Robert A. Caro

A Grand Illusion - American's Descent Into Vietnam by Robert Mann

After Tet - The Bloodiest Year In Vietnam by Ronald Spector

Nixon's Vietnam War by Jeffrey Kimball

Promise and Power - The Life and Times of Robert McNamara by Deborah Shapley

Argument Without End by Robert S. McNamara

Flawed Giant by Robert Dallek

Nixon and Kissinger - Partners in Power by Robert Dallek

Lyndon B. Johnson - Portrait of a President by Robert Dallek

Vietnam, A History by Stanley Karnow

General Maxwell Taylor - The Sword and the Pen by John M. Taylor

Waging Peace & War by Thomas J. Schoenbaum

LBJ and Vietnam by George C. Herring

Dereliction of Duty by H.R. McMaster

Combat Operations - Stemming the Tide by John M. Carland

The McNamara Ascendancy - History of the Office of the Secretary of Defense by Lawrence Kaplan, Ronald Landa and Edward Drea

Facing the Phoenix by Zalin Grant

Our Vietnam - The War 1954-1975 by A. J. Langguth

American Tragedy by David Kaiser

Senator Mansfield by Don OBerdorfer

The Living and the Dead by Paul Hendrickson

The Years of Lyndon Johnson - The Passage of Power by Robert A. Caro

PRESS ABOUT DR. WILLIAM GIBBONS

William Conrad Gibbons, author of history of the Vietnam War, dies at 88

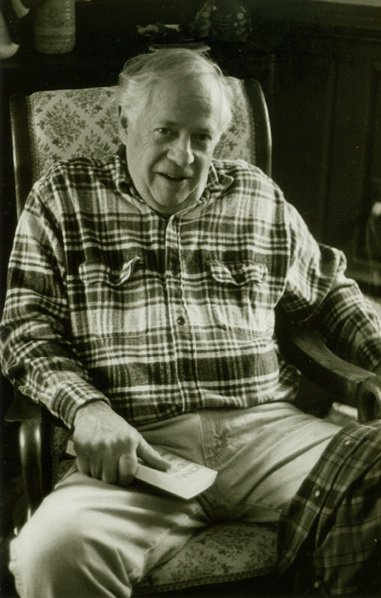

William Conrad Gibbons, a Library of Congress researcher whose multi-volume “The U.S. Government and the Vietnam War” is regarded as one of the most comprehensive histories of that divisive conflict, died July 4 at his farm in Monroe, Va. He was 88.

The cause was complications from a stroke, said his wife, Patricia Gibbons.

William Conrad Gibbons, a Library of Congress researcher whose multi-volume “The U.S. Government and the Vietnam War” is regarded as one of the most comprehensive histories of that divisive conflict, died July 4 at his farm in Monroe, Va. He was 88.

The cause was complications from a stroke, said his wife, Patricia Gibbons.

William C. Gibbons, described as a “dean” of American researchers on the Vietnam War, died July 4 at 88.

William C. Gibbons, described as a “dean” of American researchers on the Vietnam War, died July 4 at 88.

Dr. Gibbons — officially a foreign policy expert in the library’s Congressional Research Service — was tasked in 1978 with a project that would occupy him, along with an uncounted number of other scholars, for decades. At the request of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he set out to compile a complete history of the Vietnam War.

It was a monumental job. The war had claimed the lives of an estimated 3 million Vietnamese and 58,000 Americans before its end in 1975. In the United States, the conflict left painful scars among antiwar activists, who felt deceived by their government, and among veterans who perceived that their sacrifices had gone unrecognized.

Dr. Gibbons’s opus, published by the Government Printing Office and the Princeton University Press beginning in 1984, would span more than 2,000 pages in four volumes chronicling executive and legislative policymaking from 1945 to 1968. A fifth volume was in progress at the time of his death.

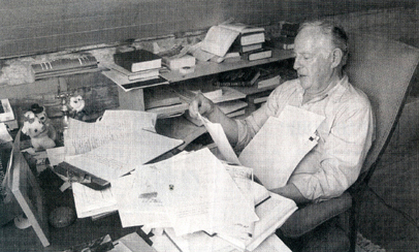

In his research, Dr. Gibbons pored over government records that filled thousands of boxes. In addition to mining documents from the White House, Congress, the military and the CIA, among other sources, he interviewed key government officials from the era. One was Robert S. McNamara, the defense secretary under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. McNamara, who died in 2009, was a principal architect of U.S. engagement in the war.

It was a monumental job. The war had claimed the lives of an estimated 3 million Vietnamese and 58,000 Americans before its end in 1975. In the United States, the conflict left painful scars among antiwar activists, who felt deceived by their government, and among veterans who perceived that their sacrifices had gone unrecognized.

Dr. Gibbons’s opus, published by the Government Printing Office and the Princeton University Press beginning in 1984, would span more than 2,000 pages in four volumes chronicling executive and legislative policymaking from 1945 to 1968. A fifth volume was in progress at the time of his death.

In his research, Dr. Gibbons pored over government records that filled thousands of boxes. In addition to mining documents from the White House, Congress, the military and the CIA, among other sources, he interviewed key government officials from the era. One was Robert S. McNamara, the defense secretary under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. McNamara, who died in 2009, was a principal architect of U.S. engagement in the war.

Dr. Gibbons collected no royalties for book sales, according to a profile in the Boston Globe, and he received little of the attention given to historians who write for popular audiences. But many such writers credited Dr. Gibbons with amassing and arranging the primary sources that helped form the foundation of their work.

Stanley Karnow, the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian whose 1983 book “Vietnam: A History” sold millions of copies, described Dr. Gibbons’s work as “one of the most valuable studies of the formulation of Vietnam policy during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.” David Kaiser, a historian who taught at the U.S. Naval War College, once wrote in The Washington Post that Dr. Gibbons was “the dean of American Vietnam researchers.”

Lewis Sorley, a military historian who relied on Dr. Gibbons’s work, said in an interview with The Post that Dr. Gibbons was a “first-rate scholar.”

“Nowhere else has anyone assembled so much material from so many sources so authoritatively, accurately and of great utility to scholars,” Sorley said. Dr. Gibbons “demonstrated even-handedness, scholarly integrity . . . and diligence of the highest order,” Sorley added. “He was an archivist. He was a collector. He was an archaeologist of information on the Vietnam War.”

William Conrad Gibbons was born in Harrisonburg, Va., on Sept. 26, 1926. He was an Army veteran of World War II and received a bachelor’s degree in history and government in 1949 from Randolph-Macon College in Ashland, Va., and a PhD in politics from Princeton University in 1961.

He began his career on Capitol Hill, working as an aide to Sen. Mike Mansfield (D-Mont.), as a committee staff member and as an assistant to then-Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson.

Dr. Gibbons worked in Washington for the U.S. Agency for International Development and in academia, including at Texas A&M University and Wellesley College in Massachusetts, before joining the Library of Congress in 1972, according to his family. He subsequently taught at George Mason University in Fairfax, Va.

He officially retired from the library in 1989 but continued working on the war history until 2004. The Globe reported that he did much of his writing using fountain pens and legal pads.

His marriages to Joan Lyon, Doris Scherz, Catherine Kennedy and Louise Erickson ended in divorce.

Survivors include his wife of 29 years, the former Patricia McAdams of Monroe; a son from his first marriage, Rob Gibbons of Albany, Calif.; a daughter from his second marriage, Frances Meier-Gibbons of Zurich; two children from his fourth marriage, Stephen Gibbons of Kill Devil Hills, N.C., and Gayle Gibbons Madeira of New York City; and two children from his fifth marriage, Ashley Gibbons of Monroe and Justin Gibbons of Indianapolis.

His other survivors include a brother, John H. Gibbons of The Plains, Va.; a sister, Elizabeth Reynolds of St. Petersburg, Fla.; and seven grandchildren.

Decades after the end of the Vietnam War, Dr. Gibbons found enduring significance in the conflict’s history.

“Our system is such that the president has the power to get us into these things, to get us trapped. We are still making foreign policy decisions without the necessary knowledge and with the arrogance that only comes from being American,” he told the Globe in 1998. “I think we are in for some very dangerous times in the days ahead.”

Source: The Washington Post

Stanley Karnow, the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian whose 1983 book “Vietnam: A History” sold millions of copies, described Dr. Gibbons’s work as “one of the most valuable studies of the formulation of Vietnam policy during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.” David Kaiser, a historian who taught at the U.S. Naval War College, once wrote in The Washington Post that Dr. Gibbons was “the dean of American Vietnam researchers.”

Lewis Sorley, a military historian who relied on Dr. Gibbons’s work, said in an interview with The Post that Dr. Gibbons was a “first-rate scholar.”

“Nowhere else has anyone assembled so much material from so many sources so authoritatively, accurately and of great utility to scholars,” Sorley said. Dr. Gibbons “demonstrated even-handedness, scholarly integrity . . . and diligence of the highest order,” Sorley added. “He was an archivist. He was a collector. He was an archaeologist of information on the Vietnam War.”

William Conrad Gibbons was born in Harrisonburg, Va., on Sept. 26, 1926. He was an Army veteran of World War II and received a bachelor’s degree in history and government in 1949 from Randolph-Macon College in Ashland, Va., and a PhD in politics from Princeton University in 1961.

He began his career on Capitol Hill, working as an aide to Sen. Mike Mansfield (D-Mont.), as a committee staff member and as an assistant to then-Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson.

Dr. Gibbons worked in Washington for the U.S. Agency for International Development and in academia, including at Texas A&M University and Wellesley College in Massachusetts, before joining the Library of Congress in 1972, according to his family. He subsequently taught at George Mason University in Fairfax, Va.

He officially retired from the library in 1989 but continued working on the war history until 2004. The Globe reported that he did much of his writing using fountain pens and legal pads.

His marriages to Joan Lyon, Doris Scherz, Catherine Kennedy and Louise Erickson ended in divorce.

Survivors include his wife of 29 years, the former Patricia McAdams of Monroe; a son from his first marriage, Rob Gibbons of Albany, Calif.; a daughter from his second marriage, Frances Meier-Gibbons of Zurich; two children from his fourth marriage, Stephen Gibbons of Kill Devil Hills, N.C., and Gayle Gibbons Madeira of New York City; and two children from his fifth marriage, Ashley Gibbons of Monroe and Justin Gibbons of Indianapolis.

His other survivors include a brother, John H. Gibbons of The Plains, Va.; a sister, Elizabeth Reynolds of St. Petersburg, Fla.; and seven grandchildren.

Decades after the end of the Vietnam War, Dr. Gibbons found enduring significance in the conflict’s history.

“Our system is such that the president has the power to get us into these things, to get us trapped. We are still making foreign policy decisions without the necessary knowledge and with the arrogance that only comes from being American,” he told the Globe in 1998. “I think we are in for some very dangerous times in the days ahead.”

Source: The Washington Post

William Conrad Gibbons, Dogged Writer About Vietnam War, Dies at 88

William Conrad Gibbons, a foreign policy expert at the Library of Congress whose multivolume account of the relationship between Congress and the executive branch during the Vietnam War has served as a cornerstone of historical writing on the war ever since its first volume was published in 1984, died on July 4 at his farm in Monroe, Va. He was 88.

William Conrad Gibbons, a foreign policy expert at the Library of Congress whose multivolume account of the relationship between Congress and the executive branch during the Vietnam War has served as a cornerstone of historical writing on the war ever since its first volume was published in 1984, died on July 4 at his farm in Monroe, Va. He was 88.

|

The cause was complications of a stroke, said his wife, Patricia McAdams Gibbons. Dr. Gibbons had nearly completed the fifth and final volume when he died.

In the late 1970s, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, seeking to map the road that had led to the morass of the Vietnam War, directed the Congressional Research Service at the Library of Congress to prepare a dispassionate, purely factual account of the period from 1945 to 1975. “Only by examining those decisions can we gain from this bitter experience the full understanding needed to act more wisely in the future,” Senator Charles H. Percy, Republican of Illinois, wrote in the foreword to the first volume of the work, “The U.S. Government and the Vietnam War: Executive and Legislative Roles and Relationships,” published by the Government Printing Office. The task fell to Dr. Gibbons, a historian by training who in 1972 had begun working as a senior analyst for the foreign affairs division at the library. With one full-time assistant, Patricia McAdams, whom he later married, he set about analyzing and organizing a mass of material, not just information on the record but also histories of the war; documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act; newly declassified material at the Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson presidential libraries; the notes of congressional committees and subcommittees; and the spoken testimony of 137 interview subjects running the gamut from Gen. William C. Westmoreland to congressional staff members. He himself had been a staff assistant to two Democratic majority leaders in the Senate, Lyndon B. Johnson and Mike Mansfield. Some subjects he spoke to were not named, like Robert S. McNamara, the defense secretary under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Johnson, whom Dr. Gibbons interviewed twice. |

“Bill knew who to talk to,” Ms. Gibbons said. “He knew who were good sources for the information.”

The resulting four volumes, more than 2,000 pages, were immediately recognized as indispensable, providing an almost day-by-day account, lavishly footnoted, of the myriad steps and countless decisions involved in a conflict whose consequences dismayed and mystified politicians and the public alike.

In keeping with its mandate, the work was descriptive and analytical. “It does not seek to judge or to assess responsibility, but it does attempt to locate responsibility, to describe roles, and to indicate why and how decisions were made,” the preface to the first volume stated.

Dr. Gibbons’s magnum opus was seized on by historians like the authors Stanley Karnow (“Vietnam: A History”), Don Oberdorfer (“Senator Mansfield”) and Robert Dallek (“Flawed Giant: Lyndon Johnson and His Times, 1961-1973”). It was an important source as well for McNamara’s memoir, “In Retrospect,” written with Brian VanDeMark.

When Princeton University Press reprinted the first two volumes in 1988, The American Historical Review wrote, “The value of William Conrad Gibbons’s study is that it follows the course of debate and decisions in Washington with measured thoroughness, presenting much the most satisfying account so far of that dimension of the conflict.”

William Conrad Gibbons was born on Sept. 26, 1926, in Harrisonburg, Va. He served in the Army at the end of World War II before earning a bachelor’s degree in history and government from Randolph-Macon College in Ashland, Va., in 1949, and a doctorate in politics from Princeton in 1961. He worked for Mansfield as well as Senator Wayne Morse, also a Democrat, after winning a congressional fellowship from the American Political Science Association. He became an assistant to Johnson in 1960 and later to Mansfield once more, when he became majority leader.

In 1962, Dr. Gibbons made an unsuccessful run for the House of Representatives from the western Virginia district that included his hometown. Returning to Washington, he served with the Agency for International Development, first as its deputy director for congressional liaison and then, from 1965 to 1968, as director.

He was hired by Texas A & M University to be the founding chairman of its political science department, and later taught as a visiting professor at Wellesley College before joining the Library of Congress. In 1980, he became a visiting professor at George Mason University. He retired from the Library of Congress in 1989 but continued writing “The U.S. Government and the Vietnam War.”

The second volume appeared in 1985, the third volume in 1988 and the fourth volume, covering July 1965 to January 1968, in 1995.

The final volume, which Dr. Gibbons left as a 747-page typed manuscript, ends at June 1971.

His wife said he had planned to continue the narrative to the end of 1971 and then write, as a kind of postscript, a slim one-volume account covering the period from 1972, when Henry A. Kissinger, then national security adviser, began conducting peace talks openly with the North Vietnamese, to the end of the war in 1975.

A spokesman for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee said the committee had not yet taken up the matter of completing the work.

In addition to his wife of 29 years, Dr. Gibbons, whose first four marriages ended in divorce, is survived by a brother, John; a sister, Elizabeth Reynolds; three sons, Rob, Stephen and Justin; three daughters, Frances Meier-Gibbons, Gayle Gibbons Madeira and Ashley Gibbons; and seven grandchildren.

“So many of these Vietnam scholars are like Bogart in ‘Treasure of the Sierra Madre,’ hoarding the gold around the campfire, saying, ‘Get away, it’s mine,’ ” said Paul Hendrickson, the author of “The Living and the Dead: Robert McNamara and Five Lives of a Lost War” (1996), which was a finalist for the National Book Award. “Bill was the opposite. He began laying documents on me that would have taken me years to get on my own through the Freedom of Information Act. His book should have been nominated for the award, not mine.”

Source: The New York Times

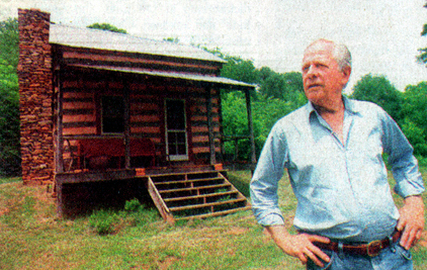

MONROE, Va. -- Nestled in a 200-year-old cabin, using aged fountain pens to fill hundreds of legal pads with a messy scrawl, William Gibbons is nearing the end of an assignment he began two decades ago. Alone, he is writing the US government history of the war in Vietnam.

Authors and scholars of the Vietnam era scramble for superlatives when asked about Gibbons and his five-volume work, "The US Government

and the Vietnam War." He has gone through thousands of boxes of government documents, interviewed the most important US officials, and laid out his findings in a comprehensive and comprehensible manner. The Gibbons volumes are "by far the best books on the subject," said William Bundy, who helped shape Vietnam policy at the State and Defense departments in the early 1960s. "They are balanced. Full. I think I can say -- and I have read a hell of a lot of stuff on the subject -- that this is the best of the breed."

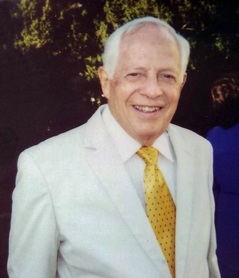

Gibbons is a courtly, sandy-haired Virginian with the tanned face, scruffy dogs, and battered pickup truck of a gentleman farmer, and the youthful attitude demanded by the two young foster children he and his wife, a Lynchburg, Va. lawyer, have adopted. His winning smile and good looks belie his 71 years and make him a natural companion to telegenic contemporaries like David McCullough or Shelby Foote.

But in an age of celebrity, Gibbons labors in anonymity. In an era of omnipresent media, Gibbons declines to practice the art of historian-as-talking-head. In a time of seven-figure book deals, his work is published quietly by the Congressional Research Service and the scholarly Princeton University Press, and he receives no royalties.

Gibbons relishes his rural corner of the Blue Ridge as "my own little world of thought, where I can figure out things." Now his scholarship is emerging as a standard reference work and foundation for a flock of popular histories and biographies. People like myself, well, just watch how much his name comes up in the footnotes."

Indeed, it is in the footnotes and acknowledgements that today's historians record their debt to Gibbons. To Boston University's Robert Dallek, who just published the second volume of his biography of Lyndon B. Johnson, Gibbons loaned his yet-unpublished manuscripts. Brian VanDeMark, who co-authored McNamara's 1995 memoir, calls Gibbons' work "magisterial," and both he and McNamara acknowledged the Virginian's help.

Stanley Karnow, author of the best-known one-volume history of the war, worked with Gibbons on the PBS television series "Vietnam: A Television History." Karnow also drew from Gibbons' "terrifically useful" manuscripts and calls the work "one of the most valuable studies of the formulation of Vietnam policy during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations."

Gibbons is not the first government historian to trace the US involvement in Vietnam. In the late 1960s, McNamara ordered his Pentagon staff to go through its files and produce a series of reports that became known, after being leaked to the press, as the Pentagon Papers amid great controversy in 1971. Each of the armed services has since studied and documented the various failings of US military strategy in Vietnam.

But such works as the Pentagon Papers "only give you a glimpse -- enough to tantalize you, make you want to fill in the blanks and put the whole thing together," Gibbons said.

Gibbons, more thoroughly than other historians, has recorded how mistakes in judgment and analysis, concerns about public opinion, and domestic politics afflicted US policymakers. He fuses poll results, White House memos, CIA analyses, congressional debate, presidential speeches, and Pentagon decision papers into a long, chilling chronological narrative that tracks the best and brightest US officials as they blunder into tragedy. His most recent volume, covering the months between July1965 and January 1968, is 969 pages long.

Some of the most poignant episodes from Gibbons' writings describe the doubts that America's leaders privately harbored and the repeated warnings they ignored as they plunged the nation into war.

For example, Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey in February 1965 urged Johnson to resist escalation and "cut our losses" in Vietnam.

"We now risk creating the impression that we are the prisoner of events in Vietnam," Humphrey wrote in a secret memo to the president. "If . . . we find ourselves leading from frustration to escalation and end up . . . embroiled deeper in fighting in Vietnam over the next few months, political opposition will steadily mount." After LBJ's landslide victory in 1964, Humphrey argued, the administration had a unique opportunity to withdraw.

Authors and scholars of the Vietnam era scramble for superlatives when asked about Gibbons and his five-volume work, "The US Government

and the Vietnam War." He has gone through thousands of boxes of government documents, interviewed the most important US officials, and laid out his findings in a comprehensive and comprehensible manner. The Gibbons volumes are "by far the best books on the subject," said William Bundy, who helped shape Vietnam policy at the State and Defense departments in the early 1960s. "They are balanced. Full. I think I can say -- and I have read a hell of a lot of stuff on the subject -- that this is the best of the breed."

Gibbons is a courtly, sandy-haired Virginian with the tanned face, scruffy dogs, and battered pickup truck of a gentleman farmer, and the youthful attitude demanded by the two young foster children he and his wife, a Lynchburg, Va. lawyer, have adopted. His winning smile and good looks belie his 71 years and make him a natural companion to telegenic contemporaries like David McCullough or Shelby Foote.

But in an age of celebrity, Gibbons labors in anonymity. In an era of omnipresent media, Gibbons declines to practice the art of historian-as-talking-head. In a time of seven-figure book deals, his work is published quietly by the Congressional Research Service and the scholarly Princeton University Press, and he receives no royalties.

Gibbons relishes his rural corner of the Blue Ridge as "my own little world of thought, where I can figure out things." Now his scholarship is emerging as a standard reference work and foundation for a flock of popular histories and biographies. People like myself, well, just watch how much his name comes up in the footnotes."

Indeed, it is in the footnotes and acknowledgements that today's historians record their debt to Gibbons. To Boston University's Robert Dallek, who just published the second volume of his biography of Lyndon B. Johnson, Gibbons loaned his yet-unpublished manuscripts. Brian VanDeMark, who co-authored McNamara's 1995 memoir, calls Gibbons' work "magisterial," and both he and McNamara acknowledged the Virginian's help.

Stanley Karnow, author of the best-known one-volume history of the war, worked with Gibbons on the PBS television series "Vietnam: A Television History." Karnow also drew from Gibbons' "terrifically useful" manuscripts and calls the work "one of the most valuable studies of the formulation of Vietnam policy during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations."

Gibbons is not the first government historian to trace the US involvement in Vietnam. In the late 1960s, McNamara ordered his Pentagon staff to go through its files and produce a series of reports that became known, after being leaked to the press, as the Pentagon Papers amid great controversy in 1971. Each of the armed services has since studied and documented the various failings of US military strategy in Vietnam.

But such works as the Pentagon Papers "only give you a glimpse -- enough to tantalize you, make you want to fill in the blanks and put the whole thing together," Gibbons said.

Gibbons, more thoroughly than other historians, has recorded how mistakes in judgment and analysis, concerns about public opinion, and domestic politics afflicted US policymakers. He fuses poll results, White House memos, CIA analyses, congressional debate, presidential speeches, and Pentagon decision papers into a long, chilling chronological narrative that tracks the best and brightest US officials as they blunder into tragedy. His most recent volume, covering the months between July1965 and January 1968, is 969 pages long.

Some of the most poignant episodes from Gibbons' writings describe the doubts that America's leaders privately harbored and the repeated warnings they ignored as they plunged the nation into war.

For example, Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey in February 1965 urged Johnson to resist escalation and "cut our losses" in Vietnam.

"We now risk creating the impression that we are the prisoner of events in Vietnam," Humphrey wrote in a secret memo to the president. "If . . . we find ourselves leading from frustration to escalation and end up . . . embroiled deeper in fighting in Vietnam over the next few months, political opposition will steadily mount." After LBJ's landslide victory in 1964, Humphrey argued, the administration had a unique opportunity to withdraw.

|

Johnson's response, Gibbons learned, was to bar Humphrey from all meetings on Vietnam for more than a year. Gibbons also shows how LBJ turned a deaf ear to the urgent warnings of CIA analysts who told the president that the US strategy, based on air power and attrition, was worse than useless -- it was counterproductive, as it stiffened Communist resolve. The CIA analysts "were ignored," Gibbons said.

Gibbons was commissioned in 1978 to write this history, as the result of a series of conversations with Norvill Jones, who led the Senate Foreign Relations Committee staff under Senator William Fulbright of Arkansas, one of the war's most outspoken opponents. |

For most of the next two decades, with the blessings of Fulbright's Republican and Democratic successors, Gibbons has worked exclusively on the Vietnam project. Having retired from the government, he is now researching and writing the fifth and final volume, chronicling the Nixon administration's handling of the war.

With top-secret security clearance and his government title, Gibbons has had superior access to documents and policymakers. But such entry has a price, Bundy acknowledged. Any work produced under "official auspices" is open to charges of being a whitewash.

When filmmaker Oliver Stone suggested in the movie "JFK" that President Kennedy was assassinated because he was ready to withdraw US troops from Vietnam, Gibbons' work was used by Stone's critics to rebut that contention. Gibbons himself then came under attack as an official apologist.

"There are those to whom `official auspices' suggests either bad writing or stereotyped thinking, neither of which is true of Bill Gibbons' books. A lot of people think that his work is not as likely to be as sprightly or original as something in the private sector," Bundy said. "But for my money, he has not had a bias nor an organizational tie that corrupts his judgment."

Gibbons has moved between government and academia during his long career. Before joining the Congressional Research Service in 1970, he worked as a Senate aide to LBJ, as a lobbyist for the Johnson administration, and as a staffer for eventual critics of the war such as Democratic Senators Mike Mansfield of Montana and Wayne Morse of Oregon. Gibbons joined the Army at age 18 during World War II, made an unsuccessful run for Congress as a Democrat in Virginia in the early 1960s, and has taught at several colleges.

Gibbons strives to meet the research service's ideal of rigid objectivity and apparently has succeeded. Even the Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman Jesse Helms of North Carolina has supported the Democrat historian's work. Gibbons used only one "confidential source" in his writing -- he says now that it was McNamara. All else is on the record. His work is checked by former officials, the Senate Foreign Relations staff, the research service, and academic specialists before publication themselves."

After studying the history of the Vietnam conflict for 20 years, Gibbons has one lesson for his countrymen: It could happen again.

Gibbons said the presidency is still "imperial," and Congress needs to assert its war-making powers over presidents prone to intervene in places like Grenada, Lebanon, Somalia, Bosnia, or Haiti.

"Our system is such that the president has the power to get us into these things, to get us trapped. We are still making foreign policy decisions without the necessary knowledge and with the arrogance that only comes from being American," said Gibbons. "I think we are in for some very dangerous times in the days ahead."

With top-secret security clearance and his government title, Gibbons has had superior access to documents and policymakers. But such entry has a price, Bundy acknowledged. Any work produced under "official auspices" is open to charges of being a whitewash.

When filmmaker Oliver Stone suggested in the movie "JFK" that President Kennedy was assassinated because he was ready to withdraw US troops from Vietnam, Gibbons' work was used by Stone's critics to rebut that contention. Gibbons himself then came under attack as an official apologist.

"There are those to whom `official auspices' suggests either bad writing or stereotyped thinking, neither of which is true of Bill Gibbons' books. A lot of people think that his work is not as likely to be as sprightly or original as something in the private sector," Bundy said. "But for my money, he has not had a bias nor an organizational tie that corrupts his judgment."

Gibbons has moved between government and academia during his long career. Before joining the Congressional Research Service in 1970, he worked as a Senate aide to LBJ, as a lobbyist for the Johnson administration, and as a staffer for eventual critics of the war such as Democratic Senators Mike Mansfield of Montana and Wayne Morse of Oregon. Gibbons joined the Army at age 18 during World War II, made an unsuccessful run for Congress as a Democrat in Virginia in the early 1960s, and has taught at several colleges.

Gibbons strives to meet the research service's ideal of rigid objectivity and apparently has succeeded. Even the Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman Jesse Helms of North Carolina has supported the Democrat historian's work. Gibbons used only one "confidential source" in his writing -- he says now that it was McNamara. All else is on the record. His work is checked by former officials, the Senate Foreign Relations staff, the research service, and academic specialists before publication themselves."

After studying the history of the Vietnam conflict for 20 years, Gibbons has one lesson for his countrymen: It could happen again.

Gibbons said the presidency is still "imperial," and Congress needs to assert its war-making powers over presidents prone to intervene in places like Grenada, Lebanon, Somalia, Bosnia, or Haiti.

"Our system is such that the president has the power to get us into these things, to get us trapped. We are still making foreign policy decisions without the necessary knowledge and with the arrogance that only comes from being American," said Gibbons. "I think we are in for some very dangerous times in the days ahead."

|

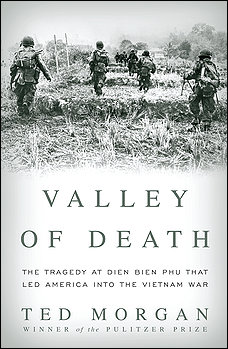

Book review: 'Valley of Death,' by Ted Morgan

Review by David Kaiser Sunday, April 4, 2010 VALLEY OF DEATH The Tragedy at Dien Bien Phu That Led America Into the Vietnam War By Ted Morgan Random House. 722 pp. $35 Ted Morgan, a retired journalist who has written numerous works of history, has now given us two books in one: an intricate, compelling narrative of the horrifying battle of Dien Bien Phu, which raged from March 13 to May 7, 1954, near the Vietnamese-Laotian border, and a parallel account of deliberations among French, American and British leaders over the impending catastrophe and what to do about it while the battle raged, and of the Geneva negotiations that eventually created North and South Vietnam. |

The battle account draws mainly on reminiscences and primary sources, while the diplomatic one uses memoirs and secondary works effectively. For his discussion of deliberations in Washington in particular, Morgan relies largely and properly on the dean of American Vietnam researchers, William Conrad Gibbons. Unfortunately his notes and bibliography attribute Gibbons's works to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, which commissioned them in the 1970s, and do not even mention that distinguished historian's name.

Morgan gives us military history of a very high quality at both the strategic and tactical levels. After seven years of war, which Morgan summarizes effectively if unevenly, Gen. Henri Navarre, the French commander in Indochina, decided in late 1953 to place a garrison of about 10,000 troops in the region. (Only a minority of them were French: The French government would not send French draftees to Indochina. The rest were Vietnamese and Laotians, mostly German members of the French Foreign Legion and other colonial troops from North Africa.) Navarre thought that by putting the base along a vital line of communication into Laos he could provoke Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap and the Viet Minh into the kind of set-piece battle at which the French so far had excelled. Even though the French would be vulnerable to attacks from the hills and would have to conduct their entire resupply by air, he counted on superior firepower to win. Like U.S. leaders a decade later, he miscalculated the capabilities of masses of dedicated Vietnamese soldiers, helped by aid from communist China, which had provided bases and weapons to the Viet Minh since 1949.

In an extraordinary feat that recalls Henry Knox's transport of artillery from Fort Ticonderoga to Boston in the winter of 1775-76, Giap's men managed to create new, invisible roads through the jungle and use manual labor and bicycles to transport heavy artillery within range of Dien Bien Phu. Once there, they dug secure emplacements into the sides of mountains -- emplacements that French air power could not reach. Then the tens of thousands of Viet Minh troops began digging trenches to within a few hundred yards of French outposts. The battle, as Morgan repeatedly notes, was similar to sieges like Verdun during World War I -- but with the horrifying difference that the French troops had no avenue of retreat. It did not take long for Viet Minh artillery fire to make the airstrip almost unusable; for much of the battle, reinforcements and supplies had to be dropped by parachute. As the French positions shrank under the weight of costly but successful Viet Minh attacks, more and more of them were occupied by the wounded. "Valley of Death" is filled with stories of horror and heroism, especially among the medical personnel, who struggled against enormous odds. The French surrendered on May 7 when they were surrounded with no room to maneuver; the 10,000 prisoners taken (out of a total of 15,000 men sent) spent months in captivity.

The weak government of French Prime Minister Joseph Laniel did nothing to avert the disaster and began to realize that it could be an excuse to wind up an unpopular war. The British government -- led in practice by Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden -- wanted a detente with Moscow and Beijing and saw no reason why France, like Britain, should not give up its Asian empire. But U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and Adm. Arthur Radford, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, wanted an allied confrontation with China over Indochina, almost surely involving the use of atomic weapons, which Dulles in fact offered to Laniel during the crisis.

Morgan shows in some detail how British and French opposition, congressional reluctance and President Dwight Eisenhower's refusal to go it alone stopped Dulles's and Radford's plans -- but Dulles still refused to sign the Geneva agreements because they gave legitimacy to yet another new communist government, that of Ho Chi Minh. Having spent months trying to arrange a coalition of Asian and Western powers to enter the war, Dulles had to be content with forming the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization after it was over -- and with using American manpower and money to try to build non-communist bastions in South Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, with decidedly mixed results. Morgan's book will be enjoyed by students of military history and will be useful to anyone curious about the bizarre atmosphere of the early, frenzied years of the Cold War.

David Kaiser is a professor at the Naval War College in Newport, R.I., and the author, most recently, of "The Road to Dallas: The Assassination of John F. Kennedy."

Morgan gives us military history of a very high quality at both the strategic and tactical levels. After seven years of war, which Morgan summarizes effectively if unevenly, Gen. Henri Navarre, the French commander in Indochina, decided in late 1953 to place a garrison of about 10,000 troops in the region. (Only a minority of them were French: The French government would not send French draftees to Indochina. The rest were Vietnamese and Laotians, mostly German members of the French Foreign Legion and other colonial troops from North Africa.) Navarre thought that by putting the base along a vital line of communication into Laos he could provoke Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap and the Viet Minh into the kind of set-piece battle at which the French so far had excelled. Even though the French would be vulnerable to attacks from the hills and would have to conduct their entire resupply by air, he counted on superior firepower to win. Like U.S. leaders a decade later, he miscalculated the capabilities of masses of dedicated Vietnamese soldiers, helped by aid from communist China, which had provided bases and weapons to the Viet Minh since 1949.

In an extraordinary feat that recalls Henry Knox's transport of artillery from Fort Ticonderoga to Boston in the winter of 1775-76, Giap's men managed to create new, invisible roads through the jungle and use manual labor and bicycles to transport heavy artillery within range of Dien Bien Phu. Once there, they dug secure emplacements into the sides of mountains -- emplacements that French air power could not reach. Then the tens of thousands of Viet Minh troops began digging trenches to within a few hundred yards of French outposts. The battle, as Morgan repeatedly notes, was similar to sieges like Verdun during World War I -- but with the horrifying difference that the French troops had no avenue of retreat. It did not take long for Viet Minh artillery fire to make the airstrip almost unusable; for much of the battle, reinforcements and supplies had to be dropped by parachute. As the French positions shrank under the weight of costly but successful Viet Minh attacks, more and more of them were occupied by the wounded. "Valley of Death" is filled with stories of horror and heroism, especially among the medical personnel, who struggled against enormous odds. The French surrendered on May 7 when they were surrounded with no room to maneuver; the 10,000 prisoners taken (out of a total of 15,000 men sent) spent months in captivity.

The weak government of French Prime Minister Joseph Laniel did nothing to avert the disaster and began to realize that it could be an excuse to wind up an unpopular war. The British government -- led in practice by Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden -- wanted a detente with Moscow and Beijing and saw no reason why France, like Britain, should not give up its Asian empire. But U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and Adm. Arthur Radford, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, wanted an allied confrontation with China over Indochina, almost surely involving the use of atomic weapons, which Dulles in fact offered to Laniel during the crisis.

Morgan shows in some detail how British and French opposition, congressional reluctance and President Dwight Eisenhower's refusal to go it alone stopped Dulles's and Radford's plans -- but Dulles still refused to sign the Geneva agreements because they gave legitimacy to yet another new communist government, that of Ho Chi Minh. Having spent months trying to arrange a coalition of Asian and Western powers to enter the war, Dulles had to be content with forming the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization after it was over -- and with using American manpower and money to try to build non-communist bastions in South Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, with decidedly mixed results. Morgan's book will be enjoyed by students of military history and will be useful to anyone curious about the bizarre atmosphere of the early, frenzied years of the Cold War.

David Kaiser is a professor at the Naval War College in Newport, R.I., and the author, most recently, of "The Road to Dallas: The Assassination of John F. Kennedy."

A Failure of Political Intelligence

by Lieutenant Colonel Alan C. Cate, US Army

Gibbons' US Government and the Vietnam War is a massive, multivolume policy history, which he originally prepared for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee while working for the Library of Congress' Congressional Research Service (CRS). Parts I through III cover 1945 to July 1965. Part V will carry the story to the 1975 communist victory. This installment, spanning July 1965 to January 1968, like its predecessors, is exhaustively researched, meticulously footnoted and written in serviceable, if uninspired, prose.

Gibbons appears to have read every extant memoir and secondary account, interviewed all available officials and ransacked many archives during his formidable research. The result is a day-by-day, blow-by-blow account of debate and decision making in Washington, D.C. At times, the effect on the reader is mind-numbing. For instance, opening at random to page 121, we encounter a recurring vignette: "December 18, 1965, the President met from 12:34 p.m. to 2:19 p.m., and from 3:10 p.m. to 5:10 p.m. with Rusk, McNamara, McGeorge Bundy, Ball and U. Alexis Johnson. . . . " Verbatim quotations from the shorthand minutes or participants' notes follow.

The book thoroughly treats the topic suggested by its subtitle. Do not, however, be misled; it provides much more as well, including rich detail on Joint Chiefs of Staff and Military Assistance Command, Vietnam perspectives; accounts of diplomatic efforts to influence our South Vietnamese allies and North Vietnamese adversaries; and examinations of public opinion and the growth of organized antiwar sentiment. As a CRS product, the book is understandably "nonpolitical" and "nonpartisan." This poses the obvious danger of draining all interest from the story.

Nevertheless, the book rewards close reading by creating a sense of immediacy and drama beneath all the memoranda, briefings and policy discussions. While Gibbons is largely content to let the protagonists' views and perspectives carry the narrative along, he inserts occasional analytic gems. One of the most ironic concerns respective US and North Vietnamese strategies to wear down each other's will. By 1966, Washington was using gradual escalation to force negotiations, while Hanoi was using the prospect of negotiations to protract the fighting. Both, of course, contributed to a standoff at an increasing level of cost and violence.(1)

The US Government and the Vietnam War also contains material on several lesser-known aspects of the Army's activities that will be of special interest to military professionals. The most embarrassing involves US Army participation in government surveillance of the domestic antiwar movement. US congressional hearings in the 1970s revealed that Army field offices maintained files on the political activities of more than 100,000 US citizens.

Even more alarming are apparent Army efforts to disrupt dissident groups. This sordid enterprise was either compounded or, alternatively, redeemed by the feeble, almost comical, "spy versus spy" nature of the operations. Antics by Army infiltrators included providing alcohol and marijuana to protesters or stealing their bus tickets to demonstrations.(2)

More edifying in many ways, yet discouraging in others, is Gibbons' discussion of a study commissioned by Army Chief of Staff General Harold K. Johnson in 1965. Uneasy with the US military attrition strategy in Vietnam, Johnson wanted a fresh look at an alternative. Gibbons characterizes the resulting "Program for the Pacification and Long-Term Development of South Vietnam"-the PROVN Report-as "one of the most important" analyses developed within or for the government during the entire war.

Produced by a group of young field grade officers, most with Vietnam advisory experience, the PROVN Report stands out as an early, clear-sighted and in-depth appreciation of not only the military, but also the national Vietnam predicament. Essentially, it posited that the United States was headed for defeat and that the only hope for victory resided in a political, not a military, response. What makes the report remarkable is that it did not prescribe a strategy of "nation building" and counterinsurgency. One may doubt whether it would have made much difference in the end, and in any event, there had always been an articulate minority, in and out of uniform, to advocate similar approaches.

Rather, it represents a respectable attempt by junior military officers to formulate a mature national Vietnam strategy without any similarly coherent strategic guidance by the nation's civilian leaders. This feature is what makes the PROVN Report's tale so ultimately discouraging, along with how senior officials quickly buried or ignored anything in the report not conforming to their preconceptions about the war.(3)

NOTES

by Lieutenant Colonel Alan C. Cate, US Army

Gibbons' US Government and the Vietnam War is a massive, multivolume policy history, which he originally prepared for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee while working for the Library of Congress' Congressional Research Service (CRS). Parts I through III cover 1945 to July 1965. Part V will carry the story to the 1975 communist victory. This installment, spanning July 1965 to January 1968, like its predecessors, is exhaustively researched, meticulously footnoted and written in serviceable, if uninspired, prose.

Gibbons appears to have read every extant memoir and secondary account, interviewed all available officials and ransacked many archives during his formidable research. The result is a day-by-day, blow-by-blow account of debate and decision making in Washington, D.C. At times, the effect on the reader is mind-numbing. For instance, opening at random to page 121, we encounter a recurring vignette: "December 18, 1965, the President met from 12:34 p.m. to 2:19 p.m., and from 3:10 p.m. to 5:10 p.m. with Rusk, McNamara, McGeorge Bundy, Ball and U. Alexis Johnson. . . . " Verbatim quotations from the shorthand minutes or participants' notes follow.

The book thoroughly treats the topic suggested by its subtitle. Do not, however, be misled; it provides much more as well, including rich detail on Joint Chiefs of Staff and Military Assistance Command, Vietnam perspectives; accounts of diplomatic efforts to influence our South Vietnamese allies and North Vietnamese adversaries; and examinations of public opinion and the growth of organized antiwar sentiment. As a CRS product, the book is understandably "nonpolitical" and "nonpartisan." This poses the obvious danger of draining all interest from the story.

Nevertheless, the book rewards close reading by creating a sense of immediacy and drama beneath all the memoranda, briefings and policy discussions. While Gibbons is largely content to let the protagonists' views and perspectives carry the narrative along, he inserts occasional analytic gems. One of the most ironic concerns respective US and North Vietnamese strategies to wear down each other's will. By 1966, Washington was using gradual escalation to force negotiations, while Hanoi was using the prospect of negotiations to protract the fighting. Both, of course, contributed to a standoff at an increasing level of cost and violence.(1)

The US Government and the Vietnam War also contains material on several lesser-known aspects of the Army's activities that will be of special interest to military professionals. The most embarrassing involves US Army participation in government surveillance of the domestic antiwar movement. US congressional hearings in the 1970s revealed that Army field offices maintained files on the political activities of more than 100,000 US citizens.

Even more alarming are apparent Army efforts to disrupt dissident groups. This sordid enterprise was either compounded or, alternatively, redeemed by the feeble, almost comical, "spy versus spy" nature of the operations. Antics by Army infiltrators included providing alcohol and marijuana to protesters or stealing their bus tickets to demonstrations.(2)

More edifying in many ways, yet discouraging in others, is Gibbons' discussion of a study commissioned by Army Chief of Staff General Harold K. Johnson in 1965. Uneasy with the US military attrition strategy in Vietnam, Johnson wanted a fresh look at an alternative. Gibbons characterizes the resulting "Program for the Pacification and Long-Term Development of South Vietnam"-the PROVN Report-as "one of the most important" analyses developed within or for the government during the entire war.

Produced by a group of young field grade officers, most with Vietnam advisory experience, the PROVN Report stands out as an early, clear-sighted and in-depth appreciation of not only the military, but also the national Vietnam predicament. Essentially, it posited that the United States was headed for defeat and that the only hope for victory resided in a political, not a military, response. What makes the report remarkable is that it did not prescribe a strategy of "nation building" and counterinsurgency. One may doubt whether it would have made much difference in the end, and in any event, there had always been an articulate minority, in and out of uniform, to advocate similar approaches.

Rather, it represents a respectable attempt by junior military officers to formulate a mature national Vietnam strategy without any similarly coherent strategic guidance by the nation's civilian leaders. This feature is what makes the PROVN Report's tale so ultimately discouraging, along with how senior officials quickly buried or ignored anything in the report not conforming to their preconceptions about the war.(3)

NOTES

- William Conrad Gibbons, The US Government and the Vietnam War: Executive and Legislative Roles and Relationships, Part IV: July 1965-January 1968 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995), 522.

- Ibid., 853-65.

- Ibid., 201-12.

Excerpts from three-day Vietnam War symposium

No Light at the End of the Tunnel: America Goes to War in Vietnam

In April 2000, Vietnam Veterans of America and the College of William and Mary sponsored Rendezvous With War, a three-day symposium which examined multiple aspects of the Vietnam War. This final installment from that symposium actually was the opening panel. In "No Light at the End of the Tunnel," veterans, historians, and journalists discussed how the French war became the American war. William and Mary history professor Ed Crapol moderated the panel. The panelists were Stanley Karnow, Pulitzer-prize-winning journalist and WWII veteran; Ronald Spector, college history professor and Marine Vietnam veteran; Retired Army Lt. Gen. Harold Moore, a First Cav battalion and brigade commander at the Ia Drang and elsewhere in Vietnam; William Conrad Gibbons, Vietnam historian and WWII veteran; and Zalin Grant, who spent five years in Vietnam, first as an intelligence officer and then as a journalist.

William Gibbons: We got into Vietnam backwards. We backed in. The story of how that happened is a tragedy, but it’s also a lesson in the faults of our system. I think the greatest fault was our culture.

We were entirely too enamored of our strengths as a nation. We were influenced by our history as a messianic nation, trying to save people from themselves. We didn’t have any limits. We ended World War II without any idea of where the limits were. When we began to look at the situation in the Far East, all we could see was that there was a need to stop what was happening.

Even George Kennan, in a memorandum to the State Department that is very little known, recommended that action be taken to keep the communists from gaining strength in Southeast Asia, because he could see from his post in Moscow what they were up to and he thought it was ominous. But you don’t make good policy that way. You don’t look at a situation and say "It’s terrible; we’ve got to do something about it." We had no guidelines. We had no limits on what we ought to do and could do, and this led us into making great mistakes.

I’ve been a student of Congress, and Congress was partly to blame. But I have not heard any of the speakers talk about Congress and its role in this. If they had listened to some of the more intelligent, far-sighted members of Congress, the Executive Branch would not have gotten us involved as they did. But the Executive Branch never listens to Congress. You make mistakes when you don’t listen to your legislators. That was one of the great difficulties.

Even some of the more conservative members of Congress were warning that this was going to be a bottomless pit and that if we got involved, we’d better be prepared for a long and costly war that would not achieve what we wanted to achieve. Our system has a lot of problems. One of the great problems is the lack of proper machinery for consulting with the public about major decisions in the foreign policy field. I think the Founding Fathers thought they were establishing a system when they provided for the Senate to play a role in the approval of treaties and with nominations, but that didn’t happen.

Because the events we became involved in became so complex and the executive establishment became so immense and so powerful, Congress didn’t keep up. Congress only professionalized its staff in about 1945-47. So Congress was not in a very good position to play an equal role. But the Executive didn’t want Congress to play an equal role, never let it play an equal role, and rejected congressional advice whenever it did not suit them.

There are lots of examples, and it’s a sad story. Most of what Mr. MacNamara calls "missed opportunities" were pointed out in 1945 and ’46 by members of Congress. He didn’t need to have a big conference in Vietnam and go through all these things they went through. He didn’t need to do that because we had them right there in black and white in the Congressional Record and in the records of the talks members of Congress had with people in the Executive Branch.

Truman should have known better. He had been a member of Congress. Of course, that often makes them resistant to congressional advice. If they’ve been a member, they don’t like to listen to them. And he was one of the worst. He rejected the advice he was getting, and he went ahead bullheadedly as only he could. He made these gigantic mistakes--he and Acheson, who was one of the worst in terms of making mistakes--and got involved far beyond what they should have. But they should have known. They shouldn’t have made the decisions they did, which led to the missed opportunities in Mr. MacNamara’s book, which I think is more "mea" than "culpa."

I think we made mistakes because we had some of the wrong premises. Our history led us to make those kinds of mistakes about what we thought we should do and could do.

No Light at the End of the Tunnel: America Goes to War in Vietnam

In April 2000, Vietnam Veterans of America and the College of William and Mary sponsored Rendezvous With War, a three-day symposium which examined multiple aspects of the Vietnam War. This final installment from that symposium actually was the opening panel. In "No Light at the End of the Tunnel," veterans, historians, and journalists discussed how the French war became the American war. William and Mary history professor Ed Crapol moderated the panel. The panelists were Stanley Karnow, Pulitzer-prize-winning journalist and WWII veteran; Ronald Spector, college history professor and Marine Vietnam veteran; Retired Army Lt. Gen. Harold Moore, a First Cav battalion and brigade commander at the Ia Drang and elsewhere in Vietnam; William Conrad Gibbons, Vietnam historian and WWII veteran; and Zalin Grant, who spent five years in Vietnam, first as an intelligence officer and then as a journalist.

William Gibbons: We got into Vietnam backwards. We backed in. The story of how that happened is a tragedy, but it’s also a lesson in the faults of our system. I think the greatest fault was our culture.

We were entirely too enamored of our strengths as a nation. We were influenced by our history as a messianic nation, trying to save people from themselves. We didn’t have any limits. We ended World War II without any idea of where the limits were. When we began to look at the situation in the Far East, all we could see was that there was a need to stop what was happening.

Even George Kennan, in a memorandum to the State Department that is very little known, recommended that action be taken to keep the communists from gaining strength in Southeast Asia, because he could see from his post in Moscow what they were up to and he thought it was ominous. But you don’t make good policy that way. You don’t look at a situation and say "It’s terrible; we’ve got to do something about it." We had no guidelines. We had no limits on what we ought to do and could do, and this led us into making great mistakes.

I’ve been a student of Congress, and Congress was partly to blame. But I have not heard any of the speakers talk about Congress and its role in this. If they had listened to some of the more intelligent, far-sighted members of Congress, the Executive Branch would not have gotten us involved as they did. But the Executive Branch never listens to Congress. You make mistakes when you don’t listen to your legislators. That was one of the great difficulties.

Even some of the more conservative members of Congress were warning that this was going to be a bottomless pit and that if we got involved, we’d better be prepared for a long and costly war that would not achieve what we wanted to achieve. Our system has a lot of problems. One of the great problems is the lack of proper machinery for consulting with the public about major decisions in the foreign policy field. I think the Founding Fathers thought they were establishing a system when they provided for the Senate to play a role in the approval of treaties and with nominations, but that didn’t happen.

Because the events we became involved in became so complex and the executive establishment became so immense and so powerful, Congress didn’t keep up. Congress only professionalized its staff in about 1945-47. So Congress was not in a very good position to play an equal role. But the Executive didn’t want Congress to play an equal role, never let it play an equal role, and rejected congressional advice whenever it did not suit them.

There are lots of examples, and it’s a sad story. Most of what Mr. MacNamara calls "missed opportunities" were pointed out in 1945 and ’46 by members of Congress. He didn’t need to have a big conference in Vietnam and go through all these things they went through. He didn’t need to do that because we had them right there in black and white in the Congressional Record and in the records of the talks members of Congress had with people in the Executive Branch.

Truman should have known better. He had been a member of Congress. Of course, that often makes them resistant to congressional advice. If they’ve been a member, they don’t like to listen to them. And he was one of the worst. He rejected the advice he was getting, and he went ahead bullheadedly as only he could. He made these gigantic mistakes--he and Acheson, who was one of the worst in terms of making mistakes--and got involved far beyond what they should have. But they should have known. They shouldn’t have made the decisions they did, which led to the missed opportunities in Mr. MacNamara’s book, which I think is more "mea" than "culpa."

I think we made mistakes because we had some of the wrong premises. Our history led us to make those kinds of mistakes about what we thought we should do and could do.

NOTE:

The information on this page is free to be shared and reproduced and is released under the Creative Commons-Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 license: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

-Gayle Gibbons Madeira